Camels are Never Cold – Freeski Mountaineering in Mongolia

In May 2013, SCOTT Team rider Liz Kristoferitsch (AUT) was part of an expedition to the Tavan Bogd mountain range in Mongolia, together with Melissa Presslaber, Michael Mayrhofer and Stephan Skrobar. She tells us about her amazing experience.

“Last spring the winter in Europe did not want to end. By the end of April there was still plenty of touring possibilities higher up in the mountains. But we had to leave- our flights were booked- and we wanted to get some more snow!

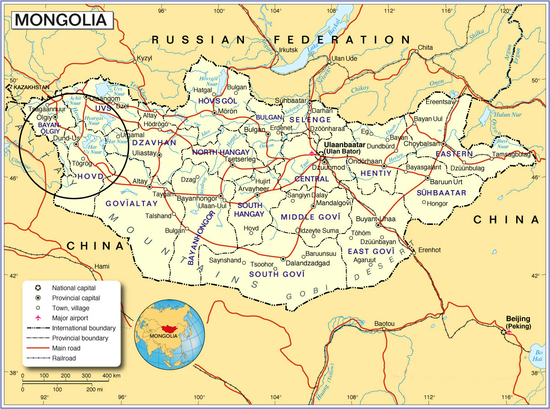

On the search for a destination for our ski trip, we had three things in mind: moving to unknown grounds, meeting a different culture and combining all of this with the possibility to hike and ski. By January the dice fell onto Mongolia. Little can be found on skiing and ski touring in this corner of the world, but the pictures and the geography of the Mongolian Altai mountain range speak for themselves. There, just on the boarder of Russia and China, the steppe meets vast glacial areas and, with a mountain range called Tavan Bogd (the Five Saints), also the highest mountains in Mongolia.

To get there, we first had to enter the country through its capital Ulan Bator (Ulaanbaatar). Here, life seems to happen in similar paths as it does in any big city- pulsating commerce, heavy traffic, pleasant nightlife and stylish young people make up the scene. Still, there is a unique contrast within the city when well-dressed businessmen walk along the sidewalk next to nomads that have just come off the steppe. Learning to read Mongolian requires a bit of time, as the letters are Russian, so first you have to learn the alphabet. Speaking did not seem to be easier, and we felt lucky enough to get around and organize our daily needs in English.

Leaving the city towards the western provinces the next day, this familiar urban scene would stop at once. Communication in the province towns or villages was a far greater challenge than it was in the capital. The five hour flight across the country provided a good impression on the vastness of the wilderness and its impressive size. Mongolia has the world´s lowest population density with 3 million inhabitants on an area three times the size of France. The country´s nomadic past has protected the country from overdevelopment, while shamanic prohibitions against defiling the earth have helped to preserve the virgin landscape and abundant wildlife. Living with and from livestock, cities and infrastructures were simply not required. Today, horses, yaks and camels are still important for transportation- the horse to human ratio in Mongolia is 13:1. On the grasslands and steppes, we learned that the wind usually blows strong all day long turning the kids ‘cheeks a sweet reddish. Seeing the outfits of the local people, they obviously enjoyed the warm spring temperatures. We, however, thankfully wore our insulation down jackets.

Beforehand we had planned everything in detail, and the cooperation with a local travel agency made it possible to get everything organized in the short time of 4 weeks. To find shops for food and isobutane can turn out very hard otherwise, as can be renting a car and driver, or fixing a date for the camels to carry bags and food for 8 people up to the base camp. Isobutane cartridges for example, had to be bought in the capital and sent overland to the western province before we actually got to Mongolia. It is a thing you cannot buy outside the capital, and bringing it along on the inland flight would not have made a good impression at the security check.

The Tavan Bogd mountain range we aimed for is formed by the Alexander and the Potanin glacier, with numerous peaks on each sides. Where the two glaciers meet was a good spot to set up camp, from here most summits lay within the range of a day’s hike. Detailed on-hand information was rare and topographic maps unavailable, proper plans for what mountains to climb or where to ski down had to be made on spot. We made decisions from home with the help of a precise weather report and a profound avalanche bulletin. We studied detailed maps to estimate ascend times and the nature of the terrain, furthermore most mountains are described in touring books or the internet. The challenge on the spot was then to find appropriate destinations and activities without this kind of luxury. In these surroundings we felt lucky enough to receive a basic three-day-weather report for the area sent from the Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics.

In the first week we hiked two of the Five Saints peaks, Naran and Nairamdal, which rewarded us with impressive views over the Mongolian glacier steppes, and gave a glance to the mountains of Russia and China. Initially, we had hoped for bigger amounts of snow- but skiing was possible, it was fun, and everyone on the team enjoyed some really good turns during the trip. Personally, the isolation of the area increased the awareness and intensity of every step and every turn we made.

After we had spent a week in the area, the weather turned. While outside a severe snowstorm hauled, we discovered the great advantages of the traditional Mongolian housing. The Ger’s felt walls sheltered us from the elements and a stove in the middle spread a luxurious heat, producing steamed dumplings filled with mutton and fried unleavened bread. In spite of this comfort, playing cards still felt nicer with gloves on.

Three days later the sky cleared up again, all grasslands around the camp had turned white. The fresh snow lifted the atmosphere and drew hopeful smiles on our faces. Short climbs the next days were rewarded with powdery turns. Now conditions even looked stable enough to reach Mongolia´s highest peak, Khuiten, and ski its Northeast face. Full of energy after resting for so long, we set off. The ascent went smoothly until we reached the ridge when all of a sudden the weather changed. Strong winds and fog came in from the West, the decision to withdraw was an easy one under these circumstances.

As with many things in life, some of our plans we succeed, and some we don´t. On the one hand we had planned to reach more summits and ski more lines. But we were allowed to get to know a different lifestyle, watch deeply colored sunsets over the grasslands and discuss the shapes of our skis with the local people. We could experience an intense time combining travelling and skiing, and that makes up for everything.”

Photos: Zlu Haller

Watch the trailer here!